Making improvements

This page provides guidance on how to go about making an improvement and solving your problem. Making an improvement involves identifying problems in your current practice, generating ideas for improvements and performing Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycles using improvement science.

Improvement science refers to the methodology, tools and processes commonly used in healthcare to improve safety and quality structures, processes and outcomes.

If you are new to improvement science or would like to refresh your knowledge, visit the CEC Academy to access a wide range of tools and resources to support your improvement journey.

You can also contact your Clinical Governance or Patient Safety Unit who can connect you with your local quality improvement experts.

What is your improvement project aiming to achieve?

Once you have established the problem you want to solve, you need to develop an aim for what the improvement project will achieve.

The aim statement captures the goal of the project and is the answer to the first question in the Model for Improvement 'What are we trying to accomplish?' The aim statement must address the problem and must not include any solutions.

The project's aim must be:

Tips:

- Remember, 'some' or 'better' is not a measure and 'soon' is not a time frame.

- Start small and focus on an individual unit or ward (even if the problem may be more widespread). This will allow you to refine the new processes, demonstrate their impact on practices and outcomes, and build increased support with stakeholders. Then you can consider spreading the initiative to other parts of your service.

- Avoid aim statements that suggest the desired solution to the problem e.g. to implement a specific policy or process on your ward.

Examples of aim statement include:

- Within 12 months, reduce seclusions to zero in the Mental Health Intensive Care Unit.

- Within 9 months, reduce seclusion rates for inpatients at psychiatric unit xx from a baseline of 136 to less than 110 per 1000 occupied beds days

- Reduce the use of seclusion by 60% in the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatient Unit at Children's Hospital, within 6 months.

What is your current seclusion reduction practice?

It is important to review and understand your current practice to help identify problems or gaps.

Develop a flow chart (a process map) of your current seclusion reduction practices. Your flow chart is a diagram which should show each step and decision related to an episode of seclusion, from the time a consumer enters your ward/facility, until they are discharged/referred.

The flow chart provides a helicopter view of how the current process happens, rather than what it should be, identifying all the points of decision-making and variation. Creating a flow chart will help the project team to:

- Visualise the entire seclusion reduction process as it currently is

- Consider the current roles and responsibilities of each member of the team (e.g. ED or admitting medical officer, nursing, allied health, peer support worker, carer/ family member etc) involved in the care of the consumer

- Identify critical points, gaps, patient journeys, decision points, variations in practice, bottlenecks and opportunities for improvement

- Highlight area of the process that have not originally been considered or are not well understood by the team

- Identify areas where data may need to be collected to demonstrate the current reliability of each step of process (that is, how often the process actually occurs as planned in practice) e.g. documentation of risk assessment, completion of safety plans, senior clinical review and rectify of the decision of seclusion, debriefing with staff and consumers/carers.

More information on flowcharts and how to construct them.

Referring to your flowchart, you will have identified potential gaps and issues with your current process for seclusion reduction. The next step is brainstorming the possible causes as to why your problem exists - Find more information on brainstorming and the 5Ws and 1H method.

Brainstorming as a team will give you a better understanding of the problem you are aiming to solve. Without understanding all the possible causes of a problem, the solutions you generate may not actually lead to an improvement because they are focused on the wrong part of the process, allowing the problem to continue.

It is important that you identify specific causes. Here are some brainstorming examples for potential problems faced in the Mental Health Inpatient setting:

Problem: "Why does the Mental Health Unit have high seclusion rate?"

How do you make sense of the problems identified?

It is essential to make meaningful sense of the causes of the problems you have identified to plan for the next stage of the improvement project. It is highly recommended that this process occurs with your team and quality improvement advisor present.

An affinity diagram involves sorting all the identified causes of the problem from the brainstorming process, into categories or themes. More information on how to create an affinity diagram.

A Driver Diagram is an extension of the Affinity Diagram. It is a visual tool that illustrates the relationship between the aim of the improvement project, the primary drivers (category headings) and the secondary drivers (causes of the problem).

Primary drivers are high-level factors that need to be influenced in order to achieve the aim. Secondary drivers are specific factors or interventions that are necessary to achieve the primary drivers. Each secondary driver will contribute to at least one primary driver, shown via relationship arrows. Information on how to create a driver diagram.

What are change ideas or change concepts?

Solutions in quality improvement are commonly referred to as change ideas or change concepts. Change ideas are well defined change concepts or interventions to address the secondary drivers, that is, what exactly are you going to do and how will this be achieved?

As a team, use the Driver Diagram to brainstorm solutions for each secondary driver. Brainstorming change ideas is the answer to the third question in the Model for Improvement 'What change can we make that will result in improvement?'.

It is possible that a solution will address more than one secondary driver. It is important to note all improvement requires change, but not all changes lead to improvement.

See Seclusion Reduction Driver Diagram example complete with change ideas.

It is not realistic or recommended to test several change ideas at once - if improvement occurs, how will you know which change idea or combination of change ideas led to the improvement? Prioritising change ideas can assist with deciding which change ideas to test first.

For each change idea, consider:

- Will it be easy or hard to implement? (consider the cost involved, time involved, extent of training required)

- What impact will it have on achieving the aim?

- Consider the feasibility, time requirements, how the change will be done (that is, the logistics) and the expected outcomes of each change idea.

Just because a change idea may be considered hard to implement does not mean it should be a low priority. Some of the hardest changes may be the most important ones to test and lead to the biggest improvement.

See Seclusion Reduction Quality Improvement Framework prioritisation matrix as a guidance.

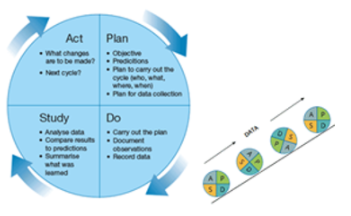

How do you test change ideas through PDSA cycles?

To determine if your change idea has led to an improvement, you should conduct quick, small-scale tests called Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) cycles.

PDSA cycle tests start on a very small scale (for example, testing a change on 1 patient or 1 shift or with 1 team) so you can test safely. If the first test leads to the predicted effect, the next test can be slightly larger (for example, testing on 3 patients, 3 shifts or 3 teams) and once there is more data and confidence in the change, increase the test size again (for example, to 5 units).

Once you have the data and confidence from these tests, the change can be rolled out and reviewed until the team can see a reliable improvement. The benefit of this is if the change doesn’t achieve the desired or expected results, you can quickly move on without having spent a huge amount of time on it or implemented it broadly.

PDSA cycles are designed to be performed rapidly and sequentially. Implementation of a change, which takes substantial time and effort, only occurs if the test of change (which starts small and gradually increases) achieve a reliable improvement. PDSA cycles are the lower part of the Model for Improvement.

You must work through each of the four stages of a PDSA cycle:

- Plan – the change (who, what, when, where and how) and make predictions about the outcome.

- Do – carry out the plan, observe and measure (that is, collect data) what happens. Take notes of what went well and what didn’t.

- Study – analyse and compare data, summarise learnings.

- Act – decide on what will be abandoned, modified or tested in a larger way for the next PDSA test using the results from the study phase.

More information on PDSA cycles.

- test no more than three change ideas at a time

- consider testing the next change idea when you are confident in the first change idea (that is, starting to scale up the testing)

- PDSA cycles are not designed to be time consuming, and can be performed rapidly and in a staggered approach

- monitor the data and measures to track improvements (refer to Data for Improvement)

- determine which changes (or combination of change ideas) are leading to an improvement and achieving the aim

- briefly document each PDSA cycle to help understand the process and ensure all four stages are followed.